Some of my research on Tolstoy can be found here.

My approach is described in the following paragraphs from my article in Kritika (Summer 2008):

Tolstoi's recognition that the work of a writer might become the coin of other realms is in sympathy with trends in contemporary criticism to read with extra-literary purpose. When he dismissed fiction for its own sake and embraced social, political, and philosophical projects, positing these as more authentic, he anticipated modes of reading that would come to the fore in the 20th century. There is relatively little scholarly work to show for this affinity, however. This is in part due to the relative lack of interest in this work in comparison to the classic fiction, but there are also historical reasons, most notably the strong Soviet bias against Tolstoi's political and religious thinking.

In early post-Soviet Russia, there was renewed interest in these latter categories, leading to the republication of many long-ignored works and, more often than not, renewal of the debates that marked their original appearance. Both in Russia and abroad, the work has been placed (or remained resting) on the same religious and political scales upon which it was first weighed: Tolstoi-heretic or saint? etc. However relevant the questions may still be, others are equally intriguing: How does Tolstoi figure in the advent of the modern subject as a political, spiritual, public, and private entity? How does he participate in the changing of the structures and dynamics of institutional authority? How does his effort to revive Christian ethics by wresting the moral subject from the authority of the Church relate to a much broader secularization of culture? How can his rejection of aristocratic art and privilege be read into a larger narrative of emerging capitalism and modernity?

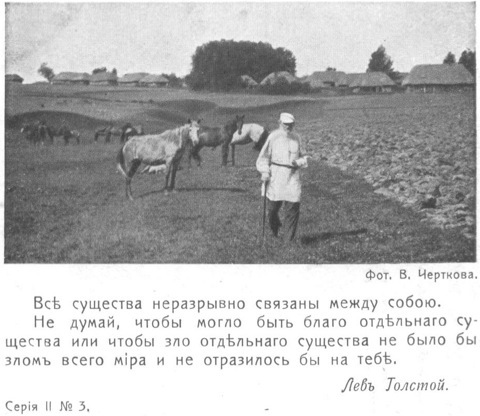

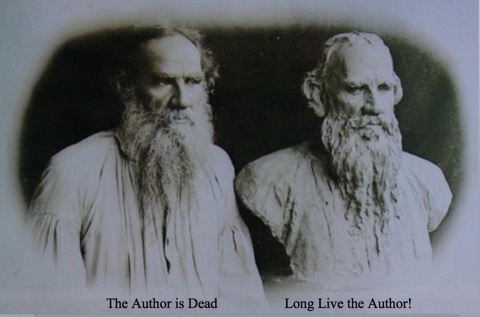

Tolstoi explored new capacities for the writer to wield moral authority in the mass media and to create vast rhetorical industries. Entering these domains brought changes to the conventional role of the author, leading to one more akin to the scriptor described by Barthes. Tolstoi's renunciation of copyright is characteristic of this process. So too are works such as Put' zhizni (The Pathway of Life) and Na kazhdyi den' (For Every Day), in which the anthological format suggests that the presented wisdom is not that of the author but an inheritance belonging to the reader. (The author is only reminding the reader of this possession.) The compiler himself is likewise supposed to claim this inheritance not as a landlord but as an equal subject of its authority. This heritage is the dominion of the "great author" in its collective, rather than singular sense, but it becomes attached specifically to Tolstoi.

In 1900, Chekhov wrote of his anxiety over the potential death of Tolstoi, who was fulfilling the charge of literature for all writers, long after he had ceased to focus on belles letters. When Nicholas II, in contrast, acknowledged Tolstoi's 1910 death by recognizing only his early literary achievements, he once again demonstrated the fateful alienation of the monarchy from the revolutionary changes that were taking place in Russian society. Literature had long been a dynamic cultural force, but Tolstoi's later work played an integral role in the vast democratization of this process. New media and new readership created new potentials for literature, and Tolstoi explored these more vigorously than any of his contemporaries. In the process he experimented with new modes of authorship, and this aspect of his work should be further explored.