Andreas Glaeser

© Andreas Glaeser, 2009-2010

Former East Germany (much like the rest of the former Soviet World) offers an incredibly fertile ground for social scientific inquiry. After one institutional order crumbled rather unexpectedly and with unimaginable speed, a ready made set of West German institutions was superimposed on the east German population. Ironically this process repeated post war experiences, when Soviet models were superimposed on the Soviet occupied lands. Surely, the incorporation of the territory and the people of the former GDR into West Germany was only imaginable under the fiction of a culturally and morally undivided nation whose congenial form was magically allowed to crystallize in the West. The West German model was thus posited as an all-German expression of social life equally valid for both parts of the German people. This move was further legitimated by the outcome of the 18 March 1990 elections in East Germany, where the electorate opted for parties who lobbied for unification by accession.

Postunification Woes:

Postunification Woes:

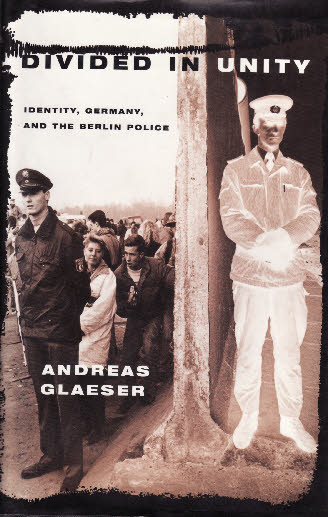

In Divided in Unity: Identity, Germany and the Berlin Police (click HERE for reference, sample chapters and reviews) I show how this conceit of an essentialistically conceived German nation has significantly contributed to the problems people experienced after unification. It led to countless misunderstandings and worse, it placed east Germans in a position which is structurally inferior to that of west Germans. Easterners were the ones who constantly had to ask how things worked, for permissions, for licenses etc., while west Germans emerged as the ones to provide the answers, grant permissions, issued licenses etc. In a paper with the title “Why Germany Remains Divided” I have called this “structural misrecognition” (references and text are HERE). Indeed, 40 years of life in very different social environments have led east and west Germans to understand the world in different terms. Two distinct cultures had indeed emerged. That these differences did not simply evaporate in two decades under a common political and economic roof owes itself precisely to the continuing placement of easterners and westerners into structurally different positions, leading to different kinds of experiences from within which other ways of seeing the world look plausible.

Emergence of a New Class Society?

More recently my interests in Germany have shifted to a different topic. The unification of Europe has contributed in many ways to the victory of neo-liberal politics in the 1990s and early 2000s. On the one side, eastern Europe as a whole lost much of its industrial base and with it countless jobs. On the other hand, the actually and constantly threatened movement of production facilities from western to eastern Europe (and the rest of the world), has weakened labor movements everywhere. I suppose it is not an accident that the inequality in income distribution in western Europe which slowly declined up until 1991 began to rise once more afterwards. In fact it looks more and more as if we are seeing the re-emergence of societies divided by class. European sociologists have invented the interesting term “precariat” to denote the new underclass and its situation. I am most interested in this context in the precise process dynamics which have led to these shifts in economic fortunes.

Cover for the book cited HERE